S&P Global report warns there is 'no easy way out' with global debt to GDP expected to increase to 366% by 2030

The world’s global debt leverage is at a higher level than pre-global financial crisis (GFC) peaks, prompting analysts to call for a “Great Reset” to mitigate the risk of more financial meltdowns.

Keeping global leverage down is no easy task and will require a number of trade-offs, according to a report by S&P Global titled Look Forward: A World in Disruption published today ahead of the World Economic Forum, which takes place in Davos, Switzerland from January 16-20.

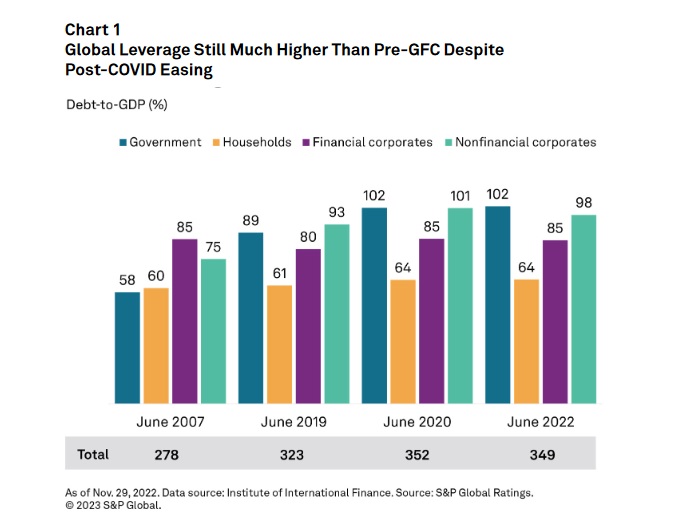

The report sets the scene by explain how global debt has hit a record US$300 trillion, or 349% leverage on gross domestic product (GDP). This translates to $37,500 of average debt for each person in the world versus GDP per capita of just $12,000. Government debt-to-GDP leverage grew aggressively, by 76%, to a total of 102%, from 2007 to 2022. The projected global debt-to-GDP ratio could reach 366% in 2030, above the 349% mark reached in June 2022.

Interestingly, while government and nonfinancial corporations’ debt soared from 76% to 102% and 31% to 98% respectively, households (up 7% to 64%) and financial sectors (stayed flat at 85%) were more conservative.

With central banks raising policy rates, investors are demanding higher yields, in response to inflation? The report, therefore, highlights 2022 as the inflexion point of the monetary environment moving away from low interest rates and easy money. “Higher yields imply a repricing of assets, while tighter money could translate to lessened market liquidity,” it stated.

The report also examined three potential scenarios for global debt leverage trend up to 2030: base case, pessimistic, and optimistic.

In its base-case scenario, it is assumed that by the conclusion of the following eight years, overall debt leverage will have increased by 5%, which is almost the same rate as the eight years prior to COVID-19's impact in 2020. Given that stronger GDP growth is anticipated in emerging nations, a minor increase in leverage can be observed relative to established markets.

The anticipated global debt-to-GDP ratio in 2030 could, therefore, might see a GDP ratio of 366% compared to the 349% in June 2022. In base case for rated sovereigns, the overall gross debt-to-GDP ratio of mature market sovereigns will slightly increase from 106% in 2022 to 107% in 2025. For new markets, the anticipated ratio is essentially unchanged at 65%.

According to the pessimistic scenario, the projected debt-to-GDP ratio could rise to a much more worrisome 391% by 2030, up 12% from the June 2022 level of 349%, if global borrowers freely take on more less-productive debt, for instance, because governments give in to populist demands or lenders are overly anxious to book assets.

But what if, according to the optimistic scenario, regulators and governments agreed to jointly manage their economies' leverage down, hoping to reach pre-COVID-19 levels by 2030? By 2030-end, the debt-to-GDP ratio could then drop by 8% to 321%.

The ratio in the first quarter of 2019 was 321%. This does not mean that no new debt is created; rather, it means that productive new debt replaces unproductive old debt

Is this optimistic scenario realistic?

During the 2020 COVID-19 crisis, governments had to spend money to sustain their economies. Less debt is required when the economy improves, which ought to help keep debt under control. Some corporations overborrowed because of the cheap interest rates and easy access to credit, so it also makes sense for lenders to limit their exposure to these high-risk borrowers.

Equity is, of course, an alternative was to finance a firm. Considering the low interest rate environment, several businesses decided to increase their leverage, whole some chose to implement share buybacks. A debt-equity rebalancing might result from the present climate of rising funding costs.

Not all debt is bad, however, and there are valid justifications for taking on more debt. Emerging markets are still making progress in terms of economic growth. Many governments could offer assistance to more disadvantaged individuals and companies so they can deal with rising food and energy prices.

Making sure that only productive new debt is deployed, paying off unproductive debt, reducing overconsumption, and restructuring loss-making businesses are possible ways to avoid the misery of a financial crisis.

Some people might not like it but a "Great Reset", in which the public accepts more prudent expenditure and policymakers are cautious about debt, is required. There is no easy way out, warns the report.