Wealth management industry analyst outlines the trends enabling customized benchmarks and the barriers to broader adoption

Last week, U.S.-based Schwab Asset Management fired a shot across the bow by announcing the launch of a new offering.

The firm unveiled plans to introduce a new direct indexing offering, Schwab Personalized Indexing, early next year. Under the program, which is currently being piloted, advisors will have the ability to adjust their clients’ allocations to three indexes – the large-cap Schwab 1000 Index, S&P Small Cap 600 Index and the MSCI KLD 400 Social Index – to align with their personal preferences or investing needs.

Schwab’s move could be a pivotal point in a growing trend predicted by Cerulli Associates. In a recent white paper, the research firm estimated that direct indexing would grow at an annualized rate of more than 12% over the next five years, compared to 3.3% for mutual funds, 11.3% for ETFs, and 9.6% for mutual funds.

“Direct indexing essentially allows investors to buy stocks of an index directly, without having to buy them in a mutual fund or ETF wrapper,” Daniel Gonzalez, an analyst who focuses on wealth management trends at Javelin Strategy & Research, told Wealth Professional in an interview. “In simplistic terms, it’s like you’re buying fruit piece by piece instead of a fruit basket, which gives you more control and personalization over your selection.”

As Gonzalez explained, the ability to create a more personalized index provides several potential benefits to investors. From a tax perspective, it opens the door to higher after-tax returns on their investments through the customized application of tax-loss harvesting strategies.

He also pointed to the recent rise in awareness around ESG. With direct indexing, investors can potentially apply their own ESG screens and tilts based on convictions they may hold around issues like climate change, human rights issues, gender equality in the workplace, and so on.

“Rather than take pre-packaged exposures of the broad market, investors could choose to lower their exposures to companies they feel are falling short, or allocate more toward the ones they feel are doing well,” he said. “They could have a better ability to invest based on their moral compass.”

Historically, Gonzalez said direct indexing strategies were available only to ultra-high-net worth investors whose investable assets allowed them to clear the high minimum thresholds required. According to Cerulli, direct indexing assets in the U.S. totalled US$362 billion as of 2020, representing nearly one fifth of the total assets in U.S. retail separate accounts.

But those barriers are poised to go down. In its announcement last week, Schwab said the minimum account size to access its direct indexing platform would be US$100,000, putting it in direct competition with a similar offering from Wealthfront, a robo-advisor rival. That’s not insignificant, but also a sizeable drop from the seven-figure minimums that were historically required.

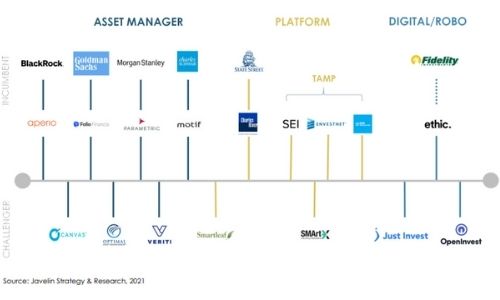

Landscape of direct indexing as of May 2021. Image sourced from the report “Javelin Strategy & Research, Direct Indexing: The Advisor, ESG, and ME” with the author’s permission.

“If you look at the direct indexing space today, you’ll see a lot of key players are starting to dabble in it, mostly through acquisitions,” Gonzalez said. “You have the likes of Goldman Sachs, BlackRock, and Morgan Stanley. In the past few months alone, JPMorgan snapped up OpenInvest, Vanguard bought Just Invest – which was its first-ever acquisition – and Franklin Templeton announced plans to acquire O’Shaugnessy Asset Management.”

Related to the trend of decreasing minimums, he said, is the gradual lowering of technological barriers. In particular, a key precursor for more retail investors to create personalized indexes is fractional share investing, which would allow them to construct broad-market indexes with a personal twist at a reasonable price point.

“The next big question is whether the Big Five Canadian banks will offer fractional share trading to the mass market,” he said. “It’s not uncommon for Canadian banks to be a couple years behind trends south of the border. But this is something that’s only going to transcend and grow.”

While he’s quick to acknowledge that direct indexing is by no means a perfect solution, he said institutional and high-net-worth clients with passive equity allocations are likely to show great interest in the tax-optimization benefits of direct indexing. Beyond that, he pointed to how trillions of dollars in generational wealth are set to change hands, which would vault ESG-minded millennial investors into a stratum of clientele for whom direct indexing could be a good fit.

“Mutual funds were the go-to vehicles for people to invest at one point, but since then they’ve embraced ETFs. Now the doors are opening to direct indexing,” Gonzalez said. “Will it dominate over ETFs? I can’t answer that. But will it take away market share in the long term? A hundred per cent, yes.”