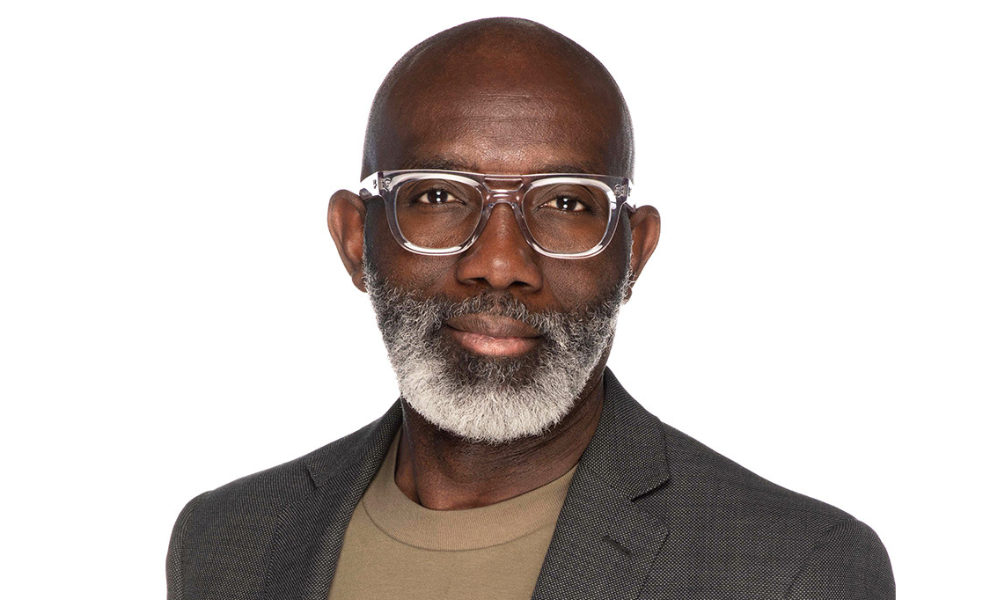

President of the firm's private equity group highlights how his firm operates as 'business builders'

In 2017, the Westinghouse Electric Company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the United States due to multibillion dollar cost overruns in two of its nuclear reactor projects. Westinghouse had been a subsidiary of Japanese industrial conglomerate Toshiba, and its business as the primary global servicer of nuclear power utilities was suffering from a secular decline in the nuclear sector. Investors saw a dying business, Brookfield saw something different.

Dave Nowak, President of Brookfield’s Private Equity Group, explains that because Brookfield owned and operated the world’s largest renewable power business they could see that Westinghouse was a far better business than its woes at the time might have indicated. The nuclear industry is extremely regulated, and Westinghouse therefore has massive competitive moats in nuclear servicing. They were guaranteed recurring business from almost every nuclear facility in the world.

Despite that appeal, Nowak and his team had to ask themselves if the nuclear industry’s secular decline was long-term. Their visibility into the renewable energy industry gave them insights nobody else had. They understood regional power markets. They understood the role nuclear played then and will play in the future. They ran models to see what would happen to key power markets if nuclear output was removed. They saw that nuclear, and therefore Westinghouse, was essential today and would be required in future. They acquired Westinghouse and took it out of bankruptcy, bringing EBITDA from $400 million to $800 million largely through operational improvements. Westinghouse, Nowak says, demonstrates how Brookfield invests.

“We're trying to invest in what we describe as essential services or products and they generally are in industries where we have an information advantage,” Nowak explains. “I ascribe to the idea that the market is a very efficient market. There are lots of smart people with lots of capital. And so how do you actually invest successfully with a risk adjusted perspective? What you're trying to find are asymmetrical returns, where there's limited downside risk, but there's much higher opportunity.”

One core tension in that approach is that the high quality businesses Brookfield wants to acquire are typically transacting at a significant premium, making asymmetrical returns harder to come by. In situations like Westinghouse, Nowak explains, Brookfield finds an information advantage. In other situations, they find meaningful ways to improve operations at a business. They seek out companies with real potential that aren’t being operated to their maximum capacity.

They drive operational improvements, Nowak explains, through the expertise of all the lawyers, investment bankers, accountants, and management consultants that Bookfield keeps on staff.

“But the fifth thing we have is we have men and women that have actually operated businesses,” Nowak says. “They've come up through industry, and that's interesting, because we have basically five different skillsets. We have multiple lenses that are just trying to get to the right answer.”

Those operators, Nowak explains, have a focus on the cost structure of the businesses Brookfield acquires. They will make decisions like bucketing capital expenditure into growth and maintenance. They tend to develop strong rapports with the CEOs and CFOs of acquired companies. They exist to differentiate Brookfield, Nowak explains, not as a private equity player that extracts value from businesses, but as a partner that builds value.

In line with that approach, Brookfield will send people from all of its skillsets into a business for a full year at least. For many of these people, who have come up through the right schools and into ideally run operations, the relative messiness of an operating business can come as a challenge. Those seconded staff are tasked with reconciling ideals of management with the reality of operations. The end result of that task, Nowak says, tends to be improved profitability and improved operations.

“That’s who we are, and that's how we drive our returns,” Nowak says. “But there's also another point to it, we pride ourselves on being responsible participants in the capital markets, okay, like we are not a one and done shop. We are franchise building enduring place, and we're a trillion dollars in AUM.”

Much of that growth, Nowak says, has been in striving to hit ‘singles and doubles’ with Brookfield’s investments. By setting achievable growth goals, generating free cash flow, and seeking asymmetrical returns, the company has been able to grow consistently while capturing the opportunity for home runs when they arise.

One such opportunity arose in a company called GrafTech, a manufacturer of graphite electrodes which are essential components in electric arc furnances. Those furnaces — common in steelmaking — burn through a graphite electrode every seven hours. While the electrodes have to be replaced, they also represent two per cent of operators’ overall costs. It’s a recurring business that customers don’t overpay for. From an investment standpoint, GrafTech is a single, maybe a double.

The company turned into a homerun as the electrification theme took hold in markets. Graphite electrodes, Nowak explains, need an input called needle coke. The other use for needle coke is in building electric car batteries. As demand for needle coke skyrocketed, the Brookfield associates seconded in GrafTech saw customers making orders a year earlier than they normally would. Customers were worried that GrafTech wouldn’t be able to keep up with the demand for Needle Coke. Rather than just bump prices up on GrafTech’s electrode capacity, the Brookfield associates decided to hold an auction for multi-year commitments. EBITDA went from $100 million to $1 billion in a year.

“It wasn't like we had this crazy investment idea where we're swinging for the fences It was because our guys were in the business every week, thinking about the business. Any other private equity group would have shown up at a quarterly board meeting, the management team would have said, ‘hey, our order book is up by 10% and they would have all done high fives,” Nowak says. “That stuff happens because you've got that operational piece. I think we're a safe pair of hands, because we're focused on not impairing capital, playing for singles and doubles. But with that operational focus, sometimes we're able to capitalize on those outsized returns.”